1.13. Object-Oriented Programming in Python: Defining Classes¶

We stated earlier that Python is an object-oriented programming language. So far, we have used a number of built-in classes to show examples of data and control structures. One of the most powerful features in an object-oriented programming language is the ability to allow a programmer (problem solver) to create new classes that model data that is needed to solve the problem.

Remember that we use abstract data types to provide the logical description of what a data object looks like (its state) and what it can do (its methods). By building a class that implements an abstract data type, a programmer can take advantage of the abstraction process and at the same time provide the details necessary to actually use the abstraction in a program. Whenever we want to implement an abstract data type, we will do so with a new class.

1.13.1. A Fraction Class¶

A very common example to show the details of implementing a user-defined

class is to construct a class to implement the abstract data type

Fraction. We have already seen that Python provides a number of

numeric classes for our use. There are times, however, that it would be

most appropriate to be able to create data objects that “look like”

fractions.

A fraction such as \(\frac {3}{5}\) consists of two parts. The top value, known as the numerator, can be any integer. The bottom value, called the denominator, can be any integer greater than 0 (negative fractions have a negative numerator). Although it is possible to create a floating point approximation for any fraction, in this case we would like to represent the fraction as an exact value.

The operations for the Fraction type will allow a Fraction data

object to behave like any other numeric value. We need to be able to

add, subtract, multiply, and divide fractions. We also want to be able

to show fractions using the standard “slash” form, for example 3/5. In

addition, all fraction methods should return results in their lowest

terms so that no matter what computation is performed, we always end up

with the most common form.

In Python, we define a new class by providing a name and a set of method definitions that are syntactically similar to function definitions. For this example,

class Fraction:

#the methods go here

provides the framework for us to define the methods. The first method

that all classes should provide is the constructor. The constructor

defines the way in which data objects are created. To create a

Fraction object, we will need to provide two pieces of data, the

numerator and the denominator. In Python, the constructor method is

always called __init__ (two underscores before and after init)

and is shown in Listing 2.

Listing 2

class Fraction:

def __init__(self,top,bottom):

self.num = top

self.den = bottom

Notice that the formal parameter list contains three items (self,

top, bottom). self is a special parameter that will always

be used as a reference back to the object itself. It must always be the

first formal parameter; however, it will never be given an actual

parameter value upon invocation. As described earlier, fractions require

two pieces of state data, the numerator and the denominator. The

notation self.num in the constructor defines the fraction object

to have an internal data object called num as part of its state.

Likewise, self.den creates the denominator. The values of the two

formal parameters are initially assigned to the state, allowing the new

fraction object to know its starting value.

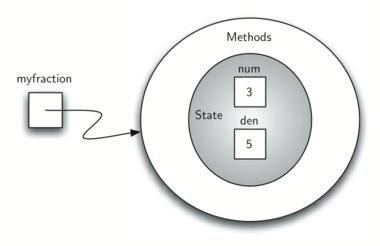

To create an instance of the Fraction class, we must invoke the

constructor. This happens by using the name of the class and passing

actual values for the necessary state (note that we never directly

invoke __init__). For example,

myfraction = Fraction(3,5)

creates an object called myfraction representing the fraction

\(\frac {3}{5}\) (three-fifths). Figure 5 shows this

object as it is now implemented.

Figure 5: An Instance of the Fraction Class

The next thing we need to do is implement the behavior that the abstract

data type requires. To begin, consider what happens when we try to print

a Fraction object.

>>> myf = Fraction(3,5)

>>> print(myf)

<__main__.Fraction instance at 0x409b1acc>

The fraction object, myf, does not know how to respond to this

request to print. The print function requires that the object

convert itself into a string so that the string can be written to the

output. The only choice myf has is to show the actual reference that

is stored in the variable (the address itself). This is not what we

want.

There are two ways we can solve this problem. One is to define a method

called show that will allow the Fraction object to print itself

as a string. We can implement this method as shown in

Listing 3. If we create a Fraction object as before, we

can ask it to show itself, in other words, print itself in the proper

format. Unfortunately, this does not work in general. In order to make

printing work properly, we need to tell the Fraction class how to

convert itself into a string. This is what the print function needs

in order to do its job.

Listing 3

def show(self):

print(self.num,"/",self.den)

>>> myf = Fraction(3,5)

>>> myf.show()

3 / 5

>>> print(myf)

<__main__.Fraction instance at 0x40bce9ac>

>>>

In Python, all classes have a set of standard methods that are provided

but may not work properly. One of these, __str__, is the method to

convert an object into a string. The default implementation for this

method is to return the instance address string as we have already seen.

What we need to do is provide a “better” implementation for this method.

We will say that this implementation overrides the previous one, or

that it redefines the method’s behavior.

To do this, we simply define a method with the name __str__ and

give it a new implementation as shown in Listing 4. This definition

does not need any other information except the special parameter

self. In turn, the method will build a string representation by

converting each piece of internal state data to a string and then

placing a / character in between the strings using string

concatenation. The resulting string will be returned any time a

Fraction object is asked to convert itself to a string. Notice the

various ways that this function is used.

Listing 4

def __str__(self):

return str(self.num)+"/"+str(self.den)

>>> myf = Fraction(3,5)

>>> print(myf)

3/5

>>> print("I ate", myf, "of the pizza")

I ate 3/5 of the pizza

>>> myf.__str__()

'3/5'

>>> str(myf)

'3/5'

>>>

We can override many other methods for our new Fraction class. Some

of the most important of these are the basic arithmetic operations. We

would like to be able to create two Fraction objects and then add

them together using the standard “+” notation. At this point, if we try

to add two fractions, we get the following:

>>> f1 = Fraction(1,4)

>>> f2 = Fraction(1,2)

>>> f1+f2

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#173>", line 1, in -toplevel-

f1+f2

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +:

'instance' and 'instance'

>>>

If you look closely at the error, you see that the problem is that the

“+” operator does not understand the Fraction operands.

We can fix this by providing the Fraction class with a method that

overrides the addition method. In Python, this method is called

__add__ and it requires two parameters. The first, self, is

always needed, and the second represents the other operand in the

expression. For example,

f1.__add__(f2)

would ask the Fraction object f1 to add the Fraction object

f2 to itself. This can be written in the standard notation,

f1+f2.

Two fractions must have the same denominator to be added. The easiest

way to make sure they have the same denominator is to simply use the

product of the two denominators as a common denominator so that

\(\frac {a}{b} + \frac {c}{d} = \frac {ad}{bd} + \frac {cb}{bd} = \frac{ad+cb}{bd}\)

The implementation is shown in Listing 5. The addition

function returns a new Fraction object with the numerator and

denominator of the sum. We can use this method by writing a standard

arithmetic expression involving fractions, assigning the result of the

addition, and then printing our result.

Listing 5

def __add__(self,otherfraction):

newnum = self.num*otherfraction.den + self.den*otherfraction.num

newden = self.den * otherfraction.den

return Fraction(newnum,newden)

>>> f1=Fraction(1,4)

>>> f2=Fraction(1,2)

>>> f3=f1+f2

>>> print(f3)

6/8

>>>

The addition method works as we desire, but one thing could be better. Note that \(6/8\) is the correct result (\(\frac {1}{4} + \frac {1}{2}\)) but that it is not in the “lowest terms” representation. The best representation would be \(3/4\). In order to be sure that our results are always in the lowest terms, we need a helper function that knows how to reduce fractions. This function will need to look for the greatest common divisor, or GCD. We can then divide the numerator and the denominator by the GCD and the result will be reduced to lowest terms.

The best-known algorithm for finding a greatest common divisor is Euclid’s Algorithm, which will be discussed in detail in Chapter 8. Euclid’s Algorithm states that the greatest common divisor of two integers \(m\) and \(n\) is \(n\) if \(n\) divides \(m\) evenly. However, if \(n\) does not divide \(m\) evenly, then the answer is the greatest common divisor of \(n\) and the remainder of \(m\) divided by \(n\). We will simply provide an iterative implementation here (see ActiveCode 1). Note that this implementation of the GCD algorithm only works when the denominator is positive. This is acceptable for our fraction class because we have said that a negative fraction will be represented by a negative numerator.

Now we can use this function to help reduce any fraction. To put a fraction in lowest terms, we will divide the numerator and the denominator by their greatest common divisor. So, for the fraction \(6/8\), the greatest common divisor is 2. Dividing the top and the bottom by 2 creates a new fraction, \(3/4\) (see Listing 6).

Listing 6

def __add__(self,otherfraction):

newnum = self.num*otherfraction.den + self.den*otherfraction.num

newden = self.den * otherfraction.den

common = gcd(newnum,newden)

return Fraction(newnum//common,newden//common)

>>> f1=Fraction(1,4)

>>> f2=Fraction(1,2)

>>> f3=f1+f2

>>> print(f3)

3/4

>>>

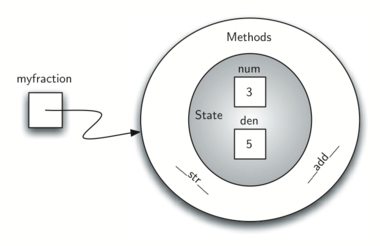

Figure 6: An Instance of the Fraction Class with Two Methods

Our Fraction object now has two very useful methods and looks

like Figure 6. An additional group of methods that we need to

include in our example Fraction class will allow two fractions to

compare themselves to one another. Assume we have two Fraction

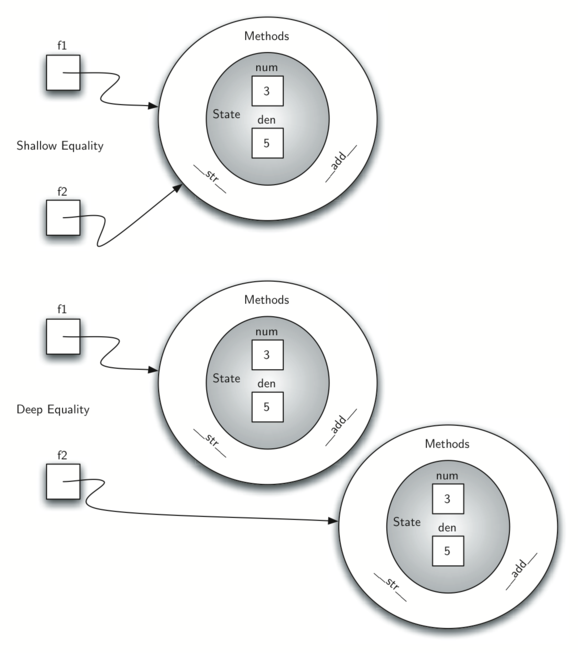

objects, f1 and f2. f1==f2 will only be True if they are

references to the same object. Two different objects with the same

numerators and denominators would not be equal under this

implementation. This is called shallow equality (see

Figure 7).

Figure 7: Shallow Equality Versus Deep Equality

We can create deep equality (see Figure 7)–equality by the

same value, not the same reference–by overriding the __eq__

method. The __eq__ method is another standard method available in

any class. The __eq__ method compares two objects and returns

True if their values are the same, False otherwise.

In the Fraction class, we can implement the __eq__ method by

again putting the two fractions in common terms and then comparing the

numerators (see Listing 7). It is important to note that there

are other relational operators that can be overridden. For example, the

__le__ method provides the less than or equal functionality.

Listing 7

def __eq__(self, other):

firstnum = self.num * other.den

secondnum = other.num * self.den

return firstnum == secondnum

The complete Fraction class, up to this point, is shown in

ActiveCode 2. We leave the remaining arithmetic and relational

methods as exercises.

Self Check

To make sure you understand how operators are implemented in Python classes, and how to properly write methods, write some methods to implement *, /, and - . Also implement comparison operators > and <

1.13.2. Inheritance: Logic Gates and Circuits¶

Our final section will introduce another important aspect of object-oriented programming. Inheritance is the ability for one class to be related to another class in much the same way that people can be related to one another. Children inherit characteristics from their parents. Similarly, Python child classes can inherit characteristic data and behavior from a parent class. These classes are often referred to as subclasses and superclasses.

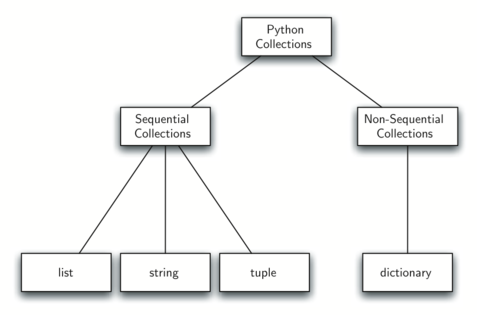

Figure 8 shows the built-in Python collections and their

relationships to one another. We call a relationship structure such as

this an inheritance hierarchy. For example, the list is a child of

the sequential collection. In this case, we call the list the child and

the sequence the parent (or subclass list and superclass sequence). This

is often referred to as an IS-A Relationship (the list IS-A

sequential collection). This implies that lists inherit important

characteristics from sequences, namely the ordering of the underlying

data and operations such as concatenation, repetition, and indexing.

Figure 8: An Inheritance Hierarchy for Python Collections

Lists, tuples, and strings are all types of sequential collections. They all inherit common data organization and operations. However, each of them is distinct based on whether the data is homogeneous and whether the collection is immutable. The children all gain from their parents but distinguish themselves by adding additional characteristics.

By organizing classes in this hierarchical fashion, object-oriented programming languages allow previously written code to be extended to meet the needs of a new situation. In addition, by organizing data in this hierarchical manner, we can better understand the relationships that exist. We can be more efficient in building our abstract representations.

To explore this idea further, we will construct a simulation, an application to simulate digital circuits. The basic building block for this simulation will be the logic gate. These electronic switches represent boolean algebra relationships between their input and their output. In general, gates have a single output line. The value of the output is dependent on the values given on the input lines.

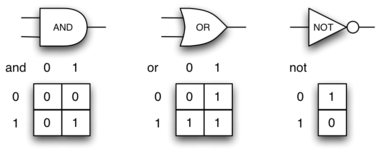

AND gates have two input lines, each of which can be either 0 or 1

(representing False or True, repectively). If both of the input

lines have the value 1, the resulting output is 1. However, if either or

both of the input lines is 0, the result is 0. OR gates also have two

input lines and produce a 1 if one or both of the input values is a 1.

In the case where both input lines are 0, the result is 0.

NOT gates differ from the other two gates in that they only have a single input line. The output value is simply the opposite of the input value. If 0 appears on the input, 1 is produced on the output. Similarly, 1 produces 0. Figure 9 shows how each of these gates is typically represented. Each gate also has a truth table of values showing the input-to-output mapping that is performed by the gate.

Figure 9: Three Types of Logic Gates

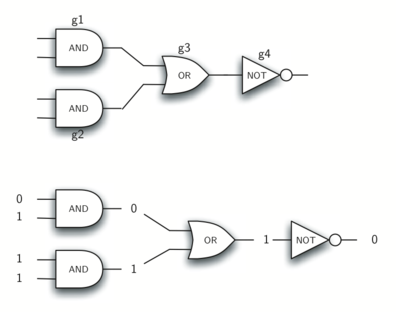

By combining these gates in various patterns and then applying a set of input values, we can build circuits that have logical functions. Figure 10 shows a circuit consisting of two AND gates, one OR gate, and a single NOT gate. The output lines from the two AND gates feed directly into the OR gate, and the resulting output from the OR gate is given to the NOT gate. If we apply a set of input values to the four input lines (two for each AND gate), the values are processed and a result appears at the output of the NOT gate. Figure 10 also shows an example with values.

Figure 10: Circuit

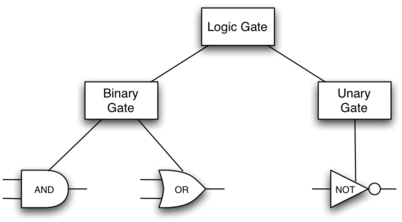

In order to implement a circuit, we will first build a representation

for logic gates. Logic gates are easily organized into a class

inheritance hierarchy as shown in Figure 11. At the top of the

hierarchy, the LogicGate class represents the most general

characteristics of logic gates: namely, a label for the gate and an

output line. The next level of subclasses breaks the logic gates into

two families, those that have one input line and those that have two.

Below that, the specific logic functions of each appear.

Figure 11: An Inheritance Hierarchy for Logic Gates

We can now start to implement the classes by starting with the most

general, LogicGate. As noted earlier, each gate has a label for

identification and a single output line. In addition, we need methods to

allow a user of a gate to ask the gate for its label.

The other behavior that every logic gate needs is the ability to know its output value. This will require that the gate perform the appropriate logic based on the current input. In order to produce output, the gate needs to know specifically what that logic is. This means calling a method to perform the logic computation. The complete class is shown in Listing 8.

Listing 8

class LogicGate:

def __init__(self,n):

self.label = n

self.output = None

def getLabel(self):

return self.label

def getOutput(self):

self.output = self.performGateLogic()

return self.output

At this point, we will not implement the performGateLogic function.

The reason for this is that we do not know how each gate will perform

its own logic operation. Those details will be included by each

individual gate that is added to the hierarchy. This is a very powerful

idea in object-oriented programming. We are writing a method that will

use code that does not exist yet. The parameter self is a reference

to the actual gate object invoking the method. Any new logic gate that

gets added to the hierarchy will simply need to implement the

performGateLogic function and it will be used at the appropriate

time. Once done, the gate can provide its output value. This ability to

extend a hierarchy that currently exists and provide the specific

functions that the hierarchy needs to use the new class is extremely

important for reusing existing code.

We categorized the logic gates based on the number of input lines. The

AND gate has two input lines. The OR gate also has two input lines. NOT

gates have one input line. The BinaryGate class will be a subclass

of LogicGate and will add two input lines. The UnaryGate class

will also subclass LogicGate but will have only a single input line.

In computer circuit design, these lines are sometimes called “pins” so

we will use that terminology in our implementation.

Listing 9

class BinaryGate(LogicGate):

def __init__(self,n):

LogicGate.__init__(self,n)

self.pinA = None

self.pinB = None

def getPinA(self):

return int(input("Enter Pin A input for gate "+ self.getLabel()+"-->"))

def getPinB(self):

return int(input("Enter Pin B input for gate "+ self.getLabel()+"-->"))

Listing 10

class UnaryGate(LogicGate):

def __init__(self,n):

LogicGate.__init__(self,n)

self.pin = None

def getPin(self):

return int(input("Enter Pin input for gate "+ self.getLabel()+"-->"))

Listing 9 and Listing 10 implement these two

classes. The constructors in both of these classes start with an

explicit call to the constructor of the parent class using the parent’s __init__

method. When creating an instance of the BinaryGate class, we

first want to initialize any data items that are inherited from

LogicGate. In this case, that means the label for the gate. The

constructor then goes on to add the two input lines (pinA and

pinB). This is a very common pattern that you should always use when

building class hierarchies. Child class constructors need to call parent

class constructors and then move on to their own distinguishing data.

Python

also has a function called super which can be used in place of explicitly

naming the parent class. This is a more general mechanism, and is widely

used, especially when a class has more than one parent. But, this is not something

we are going to discuss in this introduction. For example in our example above

LogicGate.__init__(self,n) could be replaced with super(UnaryGate,self).__init__(n).

The only behavior that the BinaryGate class adds is the ability to

get the values from the two input lines. Since these values come from

some external place, we will simply ask the user via an input statement

to provide them. The same implementation occurs for the UnaryGate

class except that there is only one input line.

Now that we have a general class for gates depending on the number of

input lines, we can build specific gates that have unique behavior. For

example, the AndGate class will be a subclass of BinaryGate

since AND gates have two input lines. As before, the first line of the

constructor calls upon the parent class constructor (BinaryGate),

which in turn calls its parent class constructor (LogicGate). Note

that the AndGate class does not provide any new data since it

inherits two input lines, one output line, and a label.

Listing 11

class AndGate(BinaryGate):

def __init__(self,n):

super(AndGate,self).__init__(self,n)

def performGateLogic(self):

a = self.getPinA()

b = self.getPinB()

if a==1 and b==1:

return 1

else:

return 0

The only thing AndGate needs to add is the specific behavior that

performs the boolean operation that was described earlier. This is the

place where we can provide the performGateLogic method. For an AND

gate, this method first must get the two input values and then only

return 1 if both input values are 1. The complete class is shown in

Listing 11.

We can show the AndGate class in action by creating an instance and

asking it to compute its output. The following session shows an

AndGate object, g1, that has an internal label "G1". When we

invoke the getOutput method, the object must first call its

performGateLogic method which in turn queries the two input lines.

Once the values are provided, the correct output is shown.

>>> g1 = AndGate("G1")

>>> g1.getOutput()

Enter Pin A input for gate G1-->1

Enter Pin B input for gate G1-->0

0

The same development can be done for OR gates and NOT gates. The

OrGate class will also be a subclass of BinaryGate and the

NotGate class will extend the UnaryGate class. Both of these

classes will need to provide their own performGateLogic functions,

as this is their specific behavior.

We can use a single gate by first constructing an instance of one of the gate classes and then asking the gate for its output (which will in turn need inputs to be provided). For example:

>>> g2 = OrGate("G2")

>>> g2.getOutput()

Enter Pin A input for gate G2-->1

Enter Pin B input for gate G2-->1

1

>>> g2.getOutput()

Enter Pin A input for gate G2-->0

Enter Pin B input for gate G2-->0

0

>>> g3 = NotGate("G3")

>>> g3.getOutput()

Enter Pin input for gate G3-->0

1

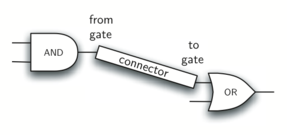

Now that we have the basic gates working, we can turn our attention to

building circuits. In order to create a circuit, we need to connect

gates together, the output of one flowing into the input of another. To

do this, we will implement a new class called Connector.

The Connector class will not reside in the gate hierarchy. It will,

however, use the gate hierarchy in that each connector will have two

gates, one on either end (see Figure 12). This relationship is

very important in object-oriented programming. It is called the HAS-A

Relationship. Recall earlier that we used the phrase “IS-A

Relationship” to say that a child class is related to a parent class,

for example UnaryGate IS-A LogicGate.

Figure 12: A Connector Connects the Output of One Gate to the Input of Another

Now, with the Connector class, we say that a Connector HAS-A

LogicGate meaning that connectors will have instances of the

LogicGate class within them but are not part of the hierarchy. When

designing classes, it is very important to distinguish between those

that have the IS-A relationship (which requires inheritance) and those

that have HAS-A relationships (with no inheritance).

Listing 12 shows the Connector class. The two gate

instances within each connector object will be referred to as the

fromgate and the togate, recognizing that data values will

“flow” from the output of one gate into an input line of the next. The

call to setNextPin is very important for making connections (see

Listing 13). We need to add this method to our gate classes so

that each togate can choose the proper input line for the

connection.

Listing 12

class Connector:

def __init__(self, fgate, tgate):

self.fromgate = fgate

self.togate = tgate

tgate.setNextPin(self)

def getFrom(self):

return self.fromgate

def getTo(self):

return self.togate

In the BinaryGate class, for gates with two possible input lines,

the connector must be connected to only one line. If both of them are

available, we will choose pinA by default. If pinA is already

connected, then we will choose pinB. It is not possible to connect

to a gate with no available input lines.

Listing 13

def setNextPin(self,source):

if self.pinA == None:

self.pinA = source

else:

if self.pinB == None:

self.pinB = source

else:

raise RuntimeError("Error: NO EMPTY PINS")

Now it is possible to get input from two places: externally, as before,

and from the output of a gate that is connected to that input line. This

requires a change to the getPinA and getPinB methods (see

Listing 14). If the input line is not connected to anything

(None), then ask the user externally as before. However, if there is

a connection, the connection is accessed and fromgate’s output value

is retrieved. This in turn causes that gate to process its logic. This

continues until all input is available and the final output value

becomes the required input for the gate in question. In a sense, the

circuit works backwards to find the input necessary to finally produce

output.

Listing 14

def getPinA(self):

if self.pinA == None:

return input("Enter Pin A input for gate " + self.getLabel()+"-->")

else:

return self.pinA.getFrom().getOutput()

The following fragment constructs the circuit shown earlier in the section:

>>> g1 = AndGate("G1")

>>> g2 = AndGate("G2")

>>> g3 = OrGate("G3")

>>> g4 = NotGate("G4")

>>> c1 = Connector(g1,g3)

>>> c2 = Connector(g2,g3)

>>> c3 = Connector(g3,g4)

The outputs from the two AND gates (g1 and g2) are connected to

the OR gate (g3) and that output is connected to the NOT gate

(g4). The output from the NOT gate is the output of the entire

circuit. For example:

>>> g4.getOutput()

Pin A input for gate G1-->0

Pin B input for gate G1-->1

Pin A input for gate G2-->1

Pin B input for gate G2-->1

0

Try it yourself using ActiveCode 4.

Self Check

Create a two new gate classes, one called NorGate the other called NandGate. NandGates work like AndGates that have a Not attached to the output. NorGates work lake OrGates that have a Not attached to the output.

Create a series of gates that prove the following equality NOT (( A and B) or (C and D)) is that same as NOT( A and B ) and NOT (C and D). Make sure to use some of your new gates in the simulation.