14. Classes and invariants¶

14.1. Private data and classes¶

We have used the word “encapsulation” in this book to refer to the process of wrapping up a sequence of instructions in a function, in order to separate the function’s interface (how to use it) from its implementation (how it does what it does).

This kind of encapsulation might be called “functional encapsulation,” to distinguish it from “data encapsulation,” which is the topic of this chapter. Data encapsulation is based on the idea that each structure definition should provide a set of functions that apply to the structure, and prevent unrestricted access to the internal representation.

One use of data encapsulation is to hide implementation details from users or programmers that don’t need to know them.

For example, there are many possible representations for a Card, including

two integers, two strings and two enumerated types. The programmer who writes

the Card member functions needs to know which implementation to use, but

someone using the Card structure should not have to know anything about its

internal structure.

As another example, we have been using string and vector objects

without ever discussing their implementations. There are many possibilities,

but as “clients” of these libraries, we don’t need to know them.

In C++, the most common way to enforce data encapsulation is to prevent client

programs from accessing instance variables of an object. The keyword

private is used to protect parts of a structure definition. For example, we

could have written the Card definition:

struct Card

{

private:

int suit, rank;

public:

Card();

Card(int s, int r);

int get_rank() const { return rank; }

int get_suit() const { return suit; }

void set_rank(int r) const { rank = r; }

void set_suit(int s) const { suit = s; }

};

There are two sections of this definition, a private part and a public part.

The functions are public, which means that they can be invoked by client

programs. The instance variables are priviate, which means that they can be

read and written only by Card member functions.

It is still possible for client programs to read and write the instance

variables using the accessor functions (the ones beginning with get

and set). It is now easy to control which operations clients can perform on

which instance variables. For example, it might be a good idea to make cards

“read only” so that after they are constructed, they cannot be changed. To do

that, all we have to do is remove the set functions.

Another advantage of using accessor functions is that we can change the internal representations of cards without having to change any client programs.

14.2. What is a class?¶

In most object-oriented programming languages, a class is a user-defined type that includes a set of functions. As we have seen, structures in C++ meet the general definition of a class.

But there is another feature in C++ that also meets this definition;

confusingly, it is called a class. In C++, a class is just a structure

whose instance variables are private by default. For example, the Card

definition from the previous section could be written:

class Card

{

int suit, rank;

public:

Card();

Card(int s, int r);

int get_rank() const { return rank; }

int get_suit() const { return suit; }

void set_rank(int r) const { rank = r; }

void set_suit(int s) const { suit = s; }

};

The word struct has been replaced with class and the label private:

removed. The result of the two definitions is exactly the same.

In fact, anything that can be written as a struct can also be written as a

class, just by adding or removing labels. There is no real reason to choose

one over the other, except that as a stylistic choice, most C++ programmers

use class.

Also, it is common to refer to all user-defined types in C++ as “classes,”

regardless of whether they are defined as a struct or a class.

14.3. Complex numbers¶

As a running example for the rest of this chapter we will consider a class definition of complex numbers. Complex numbers are useful for many branches of mathematics and engineering, and many computations are performed using complex arithmetic. A complex number is the sum of a real part and an imaginary part, and is usually written in the form \(x + yi\), where \(x\) is the real part, \(y\) the imaginary part, and \(i\) represents the square root of -1.

The following is a class definition for a user-defined type called Complex:

class Complex

{

double real, imag;

public:

Complex() { real = 0; imag = 0; }

Complex(double r, double i) { real = r; imag = i; }

};

Because this is a class definition, the instance variables real and

imag are private, and we have to include the label public: to allow

client code to invoke the constructors.

As usual, there are two constructors: one takes no arguments and initializes the instance variables to 0, the other takes two arguments and uses them to initialize the instance variables.

So far there is no real advantage to making the instance variables private. Let’s make things a little more complicated; then the point might be clearer.

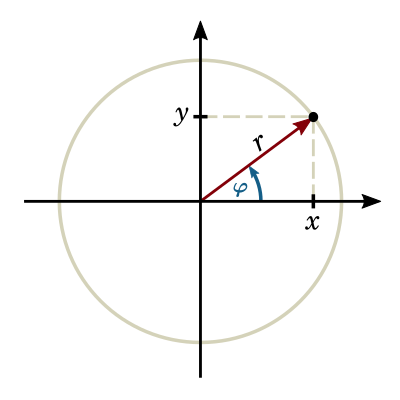

There is another common representation for complex numbers that is sometimes called “polar form” because it is based on polar coordinates. Instead of specifying the real part and the imaginary part of a point in the complex plane,polar coordinates specify the direction (or angle) of the point relative to the origin, and the distance (or magnitude) of the point.

The following figure shows the relationship between these two coordinate systems graphically.

Complex numbers in polar coordinates are written \(re^{i\theta}\), where \(r\) is the magnitude (radius), and \(\theta\) is the angle in radians.

Fortunately, it is easy to convert from one form to another. To go from Cartesian to polar:

To go from polar to Cartesian:

So which representation should we use? Well, the whole reason there are multiple representations is that some operations are easier to perform in Cartesian coordinates (like addition), and others are easier to perform in polar coordinates (like multiplication). One option is that we can write a class definition that uses both representations, and that converts between them automatically, as needed.

class Complex

{

double real, imag;

double mag, theta;

bool polar;

public:

Complex() {

real = 0; imag = 0;

polar = false;

}

Complex(double r, double i) {

real = r; imag = i;

polar = false;

}

};

There are now five instance variables, which means that this representation will take up more space than either of the others, but we will see that it is very versatile.

Four of the instance variables are self-explanatory. They contain the real

part, the imaginary part, the angle and the magnitude of the complex number.

The other variable, polar is a flag that indicates whether the polar values

are currently valid.

Since both our constructors initialize the cartesian coordinates only, new

Complex objects do not have their polar coordinates set. Setting the

polar flag to false warns other functions not to access mag or

theta until they have been set.

Now it should be clearer why we need to keep the instance variables private. If client programs were allowed unrestricted access, it would be easy for them to make errors, by reading uninitialized values. In the next few sections, we will develop accessor functions that will make those kinds of mistakes impossible.

14.4. Accessor functions¶

By convention, accessor functions have names that begin with get and

end with the name of the instance variable they fetch. The return type,

naturally, is the type of the corresponding instance variable.

double Complex::get_real()

{

return real;

}

double Complex::get_imag()

{

return imag;

}

The polar coordinates can be derived from the cartesian coordinates using the formulas presented earlier.

Here’s a calculate_polar function that does just that:

void Complex::calculate_polar()

{

mag = sqrt(real * real + imag * imag);

theta = atan(imag / real);

polar = true;

}

Now we can add accessor functions for the polar coordinates that check if

the polar flag is true before returning their values. Otherwise, we have

to call calculate_polar first.

double Complex::get_mag()

{

if (polar == false) calculate_polar();

return mag;

}

double Complex::get_theta()

{

if (polar == false) calculate_polar();

return theta;

}

14.5. Output¶

As usual when we define a new class, we want to be able to output objects in a

human-readable form. For Complex objects, we could use two functions:

string Complex::str_cartesian()

{

return to_string(get_real()) + " + " + to_string(get_imag()) + "i";

}

string Complex::str_polar()

{

string theta = to_string(get_theta());

string mag = to_string(get_mag());

return mag + "e^" + theta + "i";

}

The nice thing here is that we can output any Complex object in either

format without having to worry about the representation. Since output functions

use the accessor functions, the program will compute automatically any values

that are needed.

The following code creates a Complex object using the second constructor.

Initially, it is in Cartesian format only. When we invoke str_cartesian

it accesses real and imag without having to do any conversions.

Complex c(2, 3);

cout << c.str_cartesian() << endl;

cout << c.str_polar() << endl;

When we invoke str_polar, and str_polar invokes get_mag, the

program is forced to convert to polar coordinates and store the result in the

instance variables. The good news is that we only have to do the conversion

once. When str_polar invokes get_theta, it will see that the polar

flag gets set to true and return theta immediately.

The output of this code is:

2.000000 + 3.000000i

3.605551e^0.982794i

14.6. Overloading operators¶

Since Complex is a numeric type, we will naturally want to overload the

numeric operators for them. Let’s start with +:

Complex Complex::operator + (const Complex& c)

{

return Complex(real + c.real, imag + c.imag);

}

To invoke this function, we give send it two arguments, one on each side of

the infix + operator, just as we would with other numerical types:

Complex c1(2, 3);

Complex c2(4, 7);

Complex sum = c1 + c2;

cout << sum.str_cartesian() << endl;

The out of this code is:

6.000000 + 10.000000i

14.7. Down a rabbit hole with multiplication¶

Another operation we might want is multiplication. Unlike addition, multiplication is easy if the numbers are in polar coordinates and hard if they are in Cartesian coordinates (well, a litter harder, anyway). In polar coordinates, we can just multiply the magnitudes and add the angles.

Before we can do this, though, we are presented with a problem we need to

solve. So far we only have constructors that initialize the Cartesian

coordinates of our Complex objects.

It would be nice to add another constructor that takes the two polar values,

mag and theta, as arguments. This constructor can’t just take two

double values, however, since we can only overload a function (including

constructors) if the different versions have different signatures, the

sequence and types of their parameters. We already have a constructor for

Complex objects with two double parameters.

One solution is to add a third parameter, which we can think of as

the “flag” for polar. Let’s use an enum named Flag with the single

value POLOAR for this.

enum Flag {POLAR};

Complex::Complex(double m, double t, Flag) {

mag = m; theta = t;

polar = true;

}

With this constructor we can create Complex objects with their polar

coordinates.

Complex c1(1, 0.8, POLAR);

cout << c1.str_polar() << endl;

This code will compile and run, producing the output:

1.000000e^0.800000i

but we have introduced a dangerous bug. What will happen if we access the

Cartisian coordinates on a Complex object created using this new

constructor?

14.8. Invariants¶

There are several conditions we expect to be true for the proper use of our

Complex objects. For example, our design assumes that the Cartesian values

for real and imag always contain valid data. Polar values, on the

other hand, are not assumed to be valid unless the boolean variable polar

is set to true.

These kinds of conditions are called invariants, for the obvious reason that they do not vary - they are always supposed to be true. One of the ways to write good quality code that contains few bugs is to figure out what invariants are appropriate for your classes, and then write code that makes it impossible to violate them.

One of the primary things that data encapsulation is good for is helping to enforce invariants. The first step is to prevent unrestricted access to the instance variables by making them private. Then the only way to modify the object is through accessor functions and modifiers. If we examine all the accessors and modifiers, and we can show that every one of them maintains the invariants, then we can prove that it is impossible for an invariant to be violated.

Looking at the Complex class, we can list the functions that make

assignments to one or more instance variables in the order we developed them:

the no argument constructor

the Cartesian value constructor

calculate_polaroperator +the polar value constructor

In all but the last of these, it is straightforward to show that the function maintains the invariants:

Cartesian instance variables

realandimagcontain valid data.Polar instance variables

magandthetacontain valid data whenever the boolean instance variablepolaris set totrue.

Our new polar value constructor does not maintain the first invariant, a bug which could lead to serious problems. We have to be a little careful, though. Notice we said “maintain” the invariant. What that means is “If the invariant is true when the function is called, it will still be true when the function is complete.”

That definition allows two loopholes. First, there may be some point in the middle of the function when the invariant is not true. That’s ok, and in some cases unavoidable. As long as the invariant is restored by the end of the function, all is well.

We’ll take advantage of this first loophole to fix our polar value

constructor by having it call a new calculate_cartesian function that

sets the Cartisian instance variables based on the polar ones.

Complex::Complex(double m, double t, Flag) {

mag = m; theta = t;

polar = true;

calculate_cartesian();

}

Assuming that calculate_cartesian does what it’s supposed to do, we will

have restored the invariant. We’ll discuss this function in the next section.

The other loophole is that we only have to maintain the invariant if it was true at the beginning of the function. Otherwise, all bets are off. If the invariant was violated somewhere else in the program, usually the best we can do it dectect the error, output an error message, and exit.

14.9. Preconditions¶

Often when you write a function you make implicit assumptions about the parameters you recieve. If those assumptions turn out to be true, then everything is fine; if not, your program might crash.

To make your program more robust, it is a good idea to think about your assumptions explicitly, document them as part of the program, and maybe write code (tests) that checks them.

For an example, let’s implement our calculate_cartesian function. Is

there an assumption we need make about the current object when running this

function? Yes, we need to assume that the polar flag is set and that

mag and theta contain valid data. If that is not true, then this

function will produce meaningless results.

To protect against this, we can use the

assert function in the

assert.h header file (remember to add #include <assert.h>):

void Complex::calculate_cartesian()

{

assert(polar == true);

real = mag * cos(theta);

imag = mag * sin(theta);

}

This function first checks the status of polar by “asserting” that it must

be tree. If it is false it will cause the program to crash at runtime,

reporting that the assertion failed.

Creating a new Complex object with the Cartesian constructor and then

calling calculate_cartesian can force this behavior.

Complex c1(2, 3);

c1.calculate_cartesian();

Running this gave us:

Assertion `polar == true' failed.

Aborted (core dumped)

Now that it is safe to proceed, we can finally add the operator * function

that led us down this rabbit hole.

Complex Complex::operator * (Complex& c)

{

if (polar == false) calculate_polar();

if (c.polar == false) c.calculate_polar();

return Complex(mag * c.mag, theta + c.theta, POLAR);

}

Notice that we can not use const with the parameter c, since it may

need to be modified by the call to calculate_polar.

14.10. Private functions¶

In some cases, there are member functions that are used internally by a class,

but that should not be invoked by client programs. Our calculate_cartesian

is just such a function. If we wanted to protect these functions, we could

declare them private the same way we do with instance variables. Here’s

a complete header file, Complex.h, for our Complex objects:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <cmath>

#include <assert.h>

using namespace std;

enum Flag {POLAR};

class Complex

{

double real, imag;

double mag, theta;

bool polar;

// private accessors

void calculate_polar();

void calculate_cartesian();

public:

// constructors

Complex();

Complex(double r, double i);

Complex(double m, double t, Flag);

// accessors

double get_real();

double get_imag();

double get_mag();

double get_theta();

// member functions

Complex operator + (const Complex& c);

Complex operator * (Complex& c);

string str_cartesian();

string str_polar();

};

The following code will now give an error at compile time:

Complex c1(2, 3);

c1.calculate_cartesian();

14.11. Glossary¶

- accessor function¶

A function that provides access (read or write) to a private instance variable.

- invariant¶

A condition, usually pertaining to an object, that should be true at all times in client code, and that should be maintained by all member functions

- precondition¶

A condition that is assumed to be true at the beginning of a function. If the precondition is not true, the function may not work. It is often a good idea for functions to check their preconditions, if possible.

- postcondition¶

A condition that is true at the end of a function.