4. Conditionals, loops and exceptions¶

4.1. Conditional execution¶

4.1.1. The if statement¶

In order to write useful programs, we almost always need the ability to check conditions and change the behavior of the program accordingly. Conditional statements give us this ability. The simplest form is the if statement, which has the genaral form:

if BOOLEAN EXPRESSION:

STATEMENTS

A few important things to note about if statements:

The colon (

:) is significant and required. It separates the header of the compound statement from the body.The line after the colon must be indented. It is standard in Python to use four spaces for indenting.

All lines indented the same amount after the colon will be executed whenever the BOOLEAN_EXPRESSION is true.

Here is an example:

food = 'spam'

if food == 'spam':

print('Ummmm, my favorite!')

print('I feel like saying it 100 times...')

print(100 * (food + '! '))

The boolean expression after the if statement is called the condition.

If it is true, then all the indented statements get executed. What happens if

the condition is false, and food is not equal to 'spam'? In a simple

if statement like this, nothing happens, and the program continues on to

the next statement.

Run this example code and see what happens. Then change the value of food

to something other than 'spam' and run it again, confirming that you don’t

get any output.

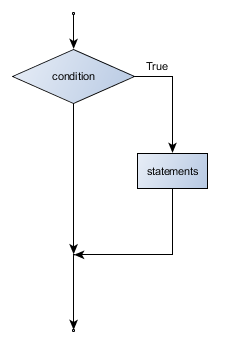

Flowchart of an if statement

As with the for statement from the last chapter, the if statement is a

compound statement. Compound statements consist of a header line and a

body. The header line of the if statement begins with the keyword if

followed by a boolean expression and ends with a colon (:).

The indented statements that follow are called a block. The first unindented statement marks the end of the block. Each statement inside the block must have the same indentation.

Indentation and the PEP 8 Python Style Guide

The Python community has developed a Style Guide for Python Code, usually referred to simply as “PEP 8”. The Python Enhancement Proposals, or PEPs, are part of the process the Python community uses to discuss and adopt changes to the language.

PEP 8 recommends the use of 4 spaces per indentation level. We will follow this (and the other PEP 8 recommendations) in this book.

To help us learn to write well styled Python code, there is a program

called pep8 that works as an

automatic style guide checker for Python source code. pep8 is

installable as a package on Debian based GNU/Linux systems like Debian.

In the Vim section of the appendix,

Configuring Debian for Python Web Development, there is instruction

on configuring vim to run pep8 on your source code with the push of a

button.

4.1.2. The if else statement¶

It is frequently the case that you want one thing to happen when a condition it

true, and something else to happen when it is false. For that we have the

if else statement.

if food == 'spam':

print('Ummmm, my favorite!')

else:

print("No, I won't have it. I want spam!")

Here, the first print statement will execute if food is equal to

'spam', and the print statement indented under the else clause will get

executed when it is not.

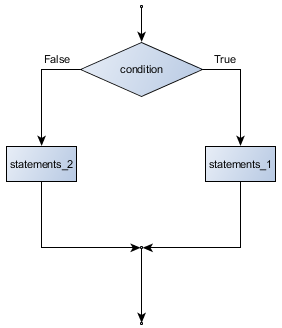

Flowchart of a if else statement

The syntax for an if else statement looks like this:

if BOOLEAN EXPRESSION:

STATEMENTS_1 # executed if condition evaluates to True

else:

STATEMENTS_2 # executed if condition evaluates to False

Each statement inside the if block of an if else statement is executed

in order if the boolean expression evaluates to True. The entire block of

statements is skipped if the boolean expression evaluates to False, and

instead all the statements under the else clause are executed.

There is no limit on the number of statements that can appear under the two

clauses of an if else statement, but there has to be at least one statement

in each block. Occasionally, it is useful to have a section with no statements

(usually as a place keeper, or scaffolding, for code you haven’t written yet).

In that case, you can use the pass statement, which does nothing except act

as a placeholder.

if True: # This is always true

pass # so this is always executed, but it does nothing

else:

pass

Python terminology

Python documentation sometimes uses the term suite of statements to mean what we have called a block here. They mean the same thing, and since most other languages and computer scientists use the word block, we’ll stick with that.

Notice too that else is not a statement. The if statement has two

clauses, one of which is the (optional) else clause. The Python

documentation calls both forms, together with the next form we are about

to meet, the if statement.

4.2. Chained conditionals¶

Sometimes there are more than two possibilities and we need more than two branches. One way to express a computation like that is a chained conditional:

if x < y:

STATEMENTS_A

elif x > y:

STATEMENTS_B

else:

STATEMENTS_C

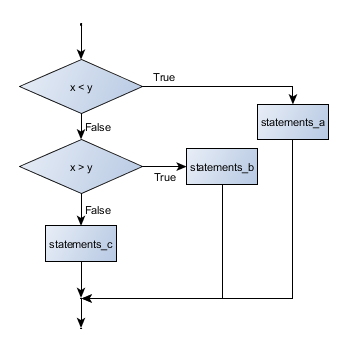

Flowchart of this chained conditional

elif is an abbreviation of else if. Again, exactly one branch will be

executed. There is no limit of the number of elif statements but only a

single (and optional) final else statement is allowed and it must be the

last branch in the statement:

if choice == 'a':

print("You chose 'a'.")

elif choice == 'b':

print("You chose 'b'.")

elif choice == 'c':

print("You chose 'c'.")

else:

print("Invalid choice.")

Each condition is checked in order. If the first is false, the next is checked, and so on. If one of them is true, the corresponding branch executes, and the statement ends. Even if more than one condition is true, only the first true branch executes.

4.3. Nested conditionals¶

One conditional can also be nested within another. (It is the same theme of composibility, again!) We could have written the previous example as follows:

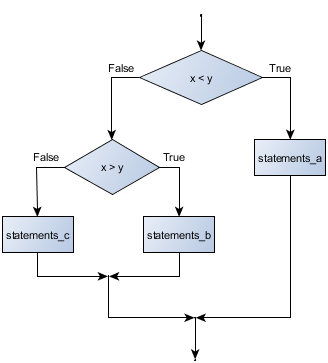

Flowchart of this nested conditional

if x < y:

STATEMENTS_A

else:

if x > y:

STATEMENTS_B

else:

STATEMENTS_C

The outer conditional contains two branches. The second branch contains

another if statement, which has two branches of its own. Those two branches

could contain conditional statements as well.

Although the indentation of the statements makes the structure apparent, nested conditionals very quickly become difficult to read. In general, it is a good idea to avoid them when you can.

Logical operators often provide a way to simplify nested conditional statements. For example, we can rewrite the following code using a single conditional:

if 0 < x: # assume x is an int here

if x < 10:

print("x is a positive single digit.")

The print function is called only if we make it past both the conditionals,

so we can use the and operator:

if 0 < x and x < 10:

print("x is a positive single digit.")

Note

Python actually allows a short hand form for this, so the following will also work:

if 0 < x < 10:

print("x is a positive single digit.")

4.4. Iteration¶

Computers are often used to automate repetitive tasks. Repeating identical or similar tasks without making errors is something that computers do well and people do poorly.

Repeated execution of a set of statements is called iteration. Python has two statements for

iteration – the for statement, which we met last chapter, and the

while statement.

Before we look at those, we need to review a few ideas.

4.4.1. Reassignmnent¶

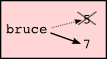

As we saw back in the Variables are variable section, it is legal to make more than one assignment to the same variable. A new assignment makes an existing variable refer to a new value (and stop referring to the old value).

bruce = 5

print(bruce)

bruce = 7

print(bruce)

The output of this program is

5

7

because the first time bruce is printed, its value is 5, and the second

time, its value is 7.

Here is what reassignment looks like in a state snapshot:

With reassignment it is especially important to distinguish between an

assignment statement and a boolean expression that tests for equality. Because

Python uses the equal token (=) for assignment,

it is tempting to interpret a statement like a = b as a boolean test.

Unlike mathematics, it is not! Remember that the Python token for the equality

operator is ==.

Note too that an equality test is symmetric, but assignment is not. For

example, if a == 7 then 7 == a. But in Python, the statement a = 7

is legal and 7 = a is not.

Furthermore, in mathematics, a statement of equality is always true. If a ==

b now, then a will always equal b. In Python, an assignment statement

can make two variables equal, but because of the possibility of reassignment,

they don’t have to stay that way:

a = 5

b = a # after executing this line, a and b are now equal

a = 3 # after executing this line, a and b are no longer equal

The third line changes the value of a but does not change the value of

b, so they are no longer equal.

Note

In some programming languages, a different symbol is used for assignment,

such as <- or :=, to avoid confusion. Python chose to use the

tokens = for assignment, and == for equality. This is a common

choice, also found in languages like C, C++, Java, JavaScript, and PHP,

though it does make things a bit confusing for new programmers.

4.4.2. Updating variables¶

When an assignment statement is executed, the right-hand-side expression (i.e. the expression that comes after the assignment token) is evaluated first. Then the result of that evaluation is written into the variable on the left hand side, thereby changing it.

One of the most common forms of reassignment is an update, where the new value of the variable depends on its old value.

n = 5

n = 3 * n + 1

The second line means “get the current value of n, multiply it by three and add

one, and put the answer back into n as its new value”. So after executing the

two lines above, n will have the value 16.

If you try to get the value of a variable that doesn’t exist yet, you’ll get an error:

>>> w = x + 1

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<interactive input>", line 1, in

NameError: name 'x' is not defined

Before you can update a variable, you have to initialize it, usually with a simple assignment:

>>> x = 0

>>> x = x + 1

This second statement — updating a variable by adding 1 to it — is very common. It is called an increment of the variable; subtracting 1 is called a decrement.

4.5. The for loop¶

The for loop processes each item in a sequence, so it is used with Python’s

sequence data types - strings, lists, and tuples.

Each item in turn is (re-)assigned to the loop variable, and the body of the loop is executed.

The general form of a for loop is:

for LOOP_VARIABLE in SEQUENCE:

STATEMENTS

This is another example of a compound statement in Python, and like the

branching statements, it has a header terminated by a colon (:) and a body

consisting of a sequence of one or more statements indented the same amount

from the header.

The loop variable is created when the for statement runs, so you do not

need to create the variable before then. Each iteration assigns the the loop

variable to the next element in the sequence, and then executes the statements

in the body. The statement finishes when the last element in the sequence is

reached.

This type of flow is called a loop because it loops back around to the top after each iteration.

for friend in ['Margot', 'Kathryn', 'Prisila']:

invitation = "Hi " + friend + ". Please come to my party on Saturday!"

print(invitation)

Running through all the items in a sequence is called traversing the sequence, or traversal.

You should run this example to see what it does.

Tip

As with all the examples you see in this book, you should try this code out yourself and see what it does. You should also try to anticipate the results before you do, and create your own related examples and try them out as well.

If you get the results you expected, pat yourself on the back and move on. If you don’t, try to figure out why. This is the essence of the scientific method, and is essential if you want to think like a computer programmer.

Often times you will want a loop that iterates a given number of times, or that

iterates over a given sequence of numbers. The range function come in handy

for that.

>>> for i in range(5):

... print('i is now:', i)

...

i is now 0

i is now 1

i is now 2

i is now 3

i is now 4

>>>

4.6. Tables¶

One of the things loops are good for is generating tables. Before computers were readily available, people had to calculate logarithms, sines and cosines, and other mathematical functions by hand. To make that easier, mathematics books contained long tables listing the values of these functions. Creating the tables was slow and boring, and they tended to be full of errors.

When computers appeared on the scene, one of the initial reactions was, “This is great! We can use the computers to generate the tables, so there will be no errors.” That turned out to be true (mostly) but shortsighted. Soon thereafter, computers and calculators were so pervasive that the tables became obsolete.

Well, almost. For some operations, computers use tables of values to get an approximate answer and then perform computations to improve the approximation. In some cases, there have been errors in the underlying tables, most famously in the table the Intel Pentium processor chip used to perform floating-point division.

Although a log table is not as useful as it once was, it still makes a good example. The following program outputs a sequence of values in the left column and 2 raised to the power of that value in the right column:

for x in range(13): # Generate numbers 0 to 12

print(x, '\t', 2**x)

Using the tab character ('\t') makes the output align nicely.

0 1

1 2

2 4

3 8

4 16

5 32

6 64

7 128

8 256

9 512

10 1024

11 2048

12 4096

4.7. The while statement¶

The general syntax for the while statement looks like this:

while BOOLEAN_EXPRESSION:

STATEMENTS

Like the branching statements and the for loop, the while statement is

a compound statement consisting of a header and a body. A while loop

executes an unknown number of times, as long at the BOOLEAN EXPRESSION is true.

Here is a simple example:

number = 0

prompt = "What is the meaning of life, the universe, and everything? "

while number != "42":

number = input(prompt)

Notice that if number is set to 42 on the first line, the body of the

while statement will not execute at all.

Here is a more elaborate example program demonstrating the use of the while

statement

name = 'Harrison'

guess = input("So I'm thinking of person's name. Try to guess it: ")

pos = 0

while guess != name and pos < len(name):

print("Nope, that's not it! Hint: letter ", end='')

print(pos + 1, "is", name[pos] + ". ", end='')

guess = input("Guess again: ")

pos = pos + 1

if pos == len(name) and name != guess:

print("Too bad, you couldn't get it. The name was", name + ".")

else:

print("\nGreat, you got it in", pos + 1, "guesses!")

The flow of execution for a while statement works like this:

Evaluate the condition (

BOOLEAN EXPRESSION), yieldingFalseorTrue.If the condition is false, exit the

whilestatement and continue execution at the next statement.If the condition is true, execute each of the

STATEMENTSin the body and then go back to step 1.

The body consists of all of the statements below the header with the same indentation.

The body of the loop should change the value of one or more variables so that eventually the condition becomes false and the loop terminates. Otherwise the loop will repeat forever, which is called an infinite loop.

An endless source of amusement for computer programmers is the observation that the directions on shampoo, lather, rinse, repeat, are an infinite loop.

In the case here, we can prove that the loop terminates because we know that

the value of len(name) is finite, and we can see that the value of pos

increments each time through the loop, so eventually it will have to equal

len(name). In other cases, it is not so easy to tell.

What you will notice here is that the while loop is more work for you —

the programmer — than the equivalent for loop. When using a while

loop one has to control the loop variable yourself: give it an initial value,

test for completion, and then make sure you change something in the body so

that the loop terminates.

4.8. Choosing between for and while¶

So why have two kinds of loop if for looks easier? This next example shows

a case where we need the extra power that we get from the while loop.

Use a for loop if you know, before you start looping, the maximum number of

times that you’ll need to execute the body. For example, if you’re traversing

a list of elements, you know that the maximum number of loop iterations you can

possibly need is “all the elements in the list”. Or if you need to print the

12 times table, we know right away how many times the loop will need to run.

So any problem like “iterate this weather model for 1000 cycles”, or “search

this list of words”, “find all prime numbers up to 10000” suggest that a

for loop is best.

By contrast, if you are required to repeat some computation until some

condition is met, and you cannot calculate in advance when this will happen, as

we did in the “greatest name” program, you’ll need a while loop.

We call the first case definite iteration — we have some definite bounds for what is needed. The latter case is called indefinite iteration — we’re not sure how many iterations we’ll need — we cannot even establish an upper bound!

4.9. Tracing a program¶

To write effective computer programs a programmer needs to develop the ability to trace the execution of a computer program. Tracing involves “becoming the computer” and following the flow of execution through a sample program run, recording the state of all variables and any output the program generates after each instruction is executed.

To understand this process, let’s trace the execution of the program from The while statement section.

At the start of the trace, we have a local variable, name with an initial

value of 'Harrison'. The user will enter a string that is stored in the

variable, guess. Let’s assume they enter 'Maribel'. The next line

creates a variable named pos and gives it an intial value of 0.

To keep track of all this as you hand trace a program, make a column heading on a piece of paper for each variable created as the program runs and another one for output. Our trace so far would look something like this:

name guess pos output

---- ----- --- ------

'Harrison' 'Maribel' 0

Since guess != name and pos < len(name) evaluates to True

(take a minute to convince yourself of this), the loop body is executed.

The user will now see

Nope, that's not it! Hint: letter 1 is 'H'. Guess again:

Assuming the user enters Karen this time, pos will be incremented,

guess != name and pos < len(name) again evaluates to True, and our

trace will now look like this:

name guess pos output

---- ----- --- ------

'Harrison' 'Maribel' 0 Nope, that's not it! Hint: letter 1 is 'H'. Guess again:

'Harrison' 'Henry' 1 Nope, that's not it! Hint: letter 2 is 'a'. Guess again:

A full trace of the program might produce something like this:

name guess pos output

---- ----- --- ------

'Harrison' 'Maribel' 0 Nope, that's not it! Hint: letter 1 is 'H'. Guess again:

'Harrison' 'Henry' 1 Nope, that's not it! Hint: letter 2 is 'a'. Guess again:

'Harrison' 'Hakeem' 2 Nope, that's not it! Hint: letter 3 is 'r'. Guess again:

'Harrison' 'Harold' 3 Nope, that's not it! Hint: letter 4 is 'r'. Guess again:

'Harrison' 'Harry' 4 Nope, that's not it! Hint: letter 5 is 'i'. Guess again:

'Harrison' 'Harrison' 5 Great, you got it in 6 guesses!

Tracing can be a bit tedious and error prone (that’s why we get computers to do this stuff in the first place!), but it is an essential skill for a programmer to have. From a trace we can learn a lot about the way our code works.

4.10. Abbreviated assignment¶

Incrementing a variable is so common that Python provides an abbreviated syntax for it:

>>> count = 0

>>> count += 1

>>> count

1

>>> count += 1

>>> count

2

count += 1 is an abreviation for count = count + 1 . We pronouce the

operator as “plus-equals”. The increment value does not have to be 1:

>>> n = 2

>>> n += 5

>>> n

7

There are similar abbreviations for -=, *=, /=, //= and %=:

>>> n = 2

>>> n *= 5

>>> n

10

>>> n -= 4

>>> n

6

>>> n //= 2

>>> n

3

>>> n %= 2

>>> n

1

4.11. Another while example: Guessing game¶

The following program implements a simple guessing game:

import random # Import the random module

number = random.randrange(1, 1000) # Get random number between [1 and 1000)

guesses = 0

guess = int(input("\nGuess my number between 1 and 1000: "))

while guess != number:

guesses += 1

if guess > number:

print(guess, "is too high.")

elif guess < number:

print(guess, "is too low.")

guess = int(input("Guess again: "))

print("\nGreat, you got it in", guesses, "guesses!\n")

This program makes use of the mathematical law of trichotomy (given real numbers a and b, exactly one of these three must be true: a > b, a < b, or a == b).

4.12. The break statement¶

The break statement is used to immediately leave the body of its loop. The next statement to be executed is the first one after the body:

for i in [12, 16, 17, 24, 29]:

if i % 2 == 1: # if the number is odd

break # immediately exit the loop

print(i)

print("done")

This prints:

12

16

done

4.13. The continue statement¶

This is a control flow statement that causes the program to immediately skip the processing of the rest of the body of the loop, for the current iteration. But the loop still carries on running for its remaining iterations:

for i in [12, 16, 17, 24, 29, 30]:

if i % 2 == 1: # if the number is odd

continue # don't process it

print(i)

print("done")

This prints:

12

16

24

30

done

4.14. An else branch in loops¶

Both for and while loops can have an optional else branch that

executes whenever the loop exits normally. The else branch does not

execute when you break from a loop, which is the reason that it is useful.

Here’s another version of the number guessing game that limits the player’s

number of guesses:

import random

number = random.randrange(1, 1000)

guesses = 1

max_guesses = 12

s = f"\nGuess my number between 1 and 1000 in {max_guesses} guesses or less: "

guess = int(input(s))

while guesses < max_guesses:

if guess == number:

print("\nGreat, you got it in", guesses, "guesses!\n")

break

if guess > number:

print(f"Your guess, {guess}, is too high.", end=' ')

else:

print(f"Your guess, {guess}, is too low.", end=' ')

print(f"{max_guesses - guesses} guesses left.")

guess = int(input("Guess again: "))

guesses += 1

else:

print(f"\nToo bad, your {max_guesses} guesses are used up!", end=" ")

print(f"My number was {number}.\n")

Compare this to the previous version and convince yourself you understand how

the else branch of the while loop works in this one.

4.15. Another for example¶

Here is an example that combines several of the things we have learned:

sentence = input('Please enter a sentence: ')

no_spaces = ''

for letter in sentence:

if letter != ' ':

no_spaces += letter

print("You sentence with spaces removed:")

print(no_spaces)

Trace this program and make sure you feel confident you understand how it works.

4.16. Nested Loops for Nested Data¶

Now we’ll come up with an even more adventurous list of structured data. In this case, we have a list of students. Each student has a name which is paired up with another list of subjects that they are enrolled for:

students = [("Alejandro", ["CompSci", "Physics"]),

("Justin", ["Math", "CompSci", "Stats"]),

("Ed", ["CompSci", "Accounting", "Economics"]),

("Margot", ["InfSys", "Accounting", "Economics", "CommLaw"]),

("Peter", ["Sociology", "Economics", "Law", "Stats", "Music"])]

Here we’ve assigned a list of five elements to the variable students.

Let’s print out each student name, and the number of subjects they are enrolled

for:

# print all students with a count of their courses.

for (name, subjects) in students:

print(name, "takes", len(subjects), "courses")

Python agreeably responds with the following output:

Aljandro takes 2 courses

Justin takes 3 courses

Ed takes 4 courses

Margot takes 4 courses

Peter takes 5 courses

Now we’d like to ask how many students are taking CompSci. This needs a counter, and for each student we need a second loop that tests each of the subjects in turn:

# Count how many students are taking CompSci

counter = 0

for (name, subjects) in students:

for s in subjects: # a nested loop!

if s == "CompSci":

counter += 1

print("The number of students taking CompSci is", counter)

The number of students taking CompSci is 3

You should set up a list of your own data that interests you — perhaps a list of your CDs, each containing a list of song titles on the CD, or a list of movie titles, each with a list of movie stars who acted in the movie. You could then ask questions like “Which movies starred Angelina Jolie?”

4.17. List comprehensions¶

A list comprehension is a syntactic construct that enables lists to be created from other lists using a compact, mathematical syntax:

>>> numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4]

>>> [x**2 for x in numbers]

[1, 4, 9, 16]

>>> [x**2 for x in numbers if x**2 > 8]

[9, 16]

>>> [(x, x**2, x**3) for x in numbers]

[(1, 1, 1), (2, 4, 8), (3, 9, 27), (4, 16, 64)]

>>> files = ['bin', 'Data', 'Desktop', '.bashrc', '.ssh', '.vimrc']

>>> [name for name in files if name[0] != '.']

['bin', 'Data', 'Desktop']

>>> letters = ['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> [n * letter for n in numbers for letter in letters]

['a', 'b', 'c', 'aa', 'bb', 'cc', 'aaa', 'bbb', 'ccc', 'aaaa', 'bbbb', 'cccc']

>>>

The general syntax for a list comprehension expression is:

[expr for item1 in seq1 for item2 in seq2 ... for itemx in seqx if condition]

This list expression has the same effect as:

output_sequence = []

for item1 in seq1:

for item2 in seq2:

...

for itemx in seqx:

if condition:

output_sequence.append(expr)

As you can see, the list comprehension is much more compact.

4.18. Exceptions¶

Back in the first chapter you were introduced to Runtime errors and promised Python’s built-in mechanism for handling them. Now we will do that.

total_pot = 200

try:

num_people = int(input('Enter the number of people to split the pot: '))

split = total_pot / num_people

print(f'Each person gets ${split:.2f}.')

except ValueError:

print('You needed to enter an integer!')

except ZeroDivisionError:

print('We can\'t divide by zero people!')

Exception handling is the process of protecting your program from exceptional conditions that occur when your program is running.

In the example above, the user is asked to enter a number of people, and that

number will be used as the donomitator of a division operator. There are

two ways the user can cause this process to go wrong. They could enter

characters that do not represent a sequence of digits of an integer, or they

could enter 0, which can not be used as the denominator of a division

operation.

To handle these exceptions, the programming statements the could generate

them are put inside a try statement. Then the anticipated possible

exceptions are handled by except statements that in this case print

and appropriate message to the program user.

The list of built-in exceptions in Python are described in The Python Standard Library reference on the Python documentation website.

4.19. Glossary¶

- append¶

To add new data to the end of a file or other data object.

- block¶

A group of consecutive statements with the same indentation.

- body¶

The block of statements in a compound statement that follows the header.

- branch¶

One of the possible paths of the flow of execution determined by conditional execution.

- chained conditional¶

A conditional branch with more than two possible flows of execution. In Python chained conditionals are written with

if ... elif ... elsestatements.- compound statement¶

A Python statement that has two parts: a header and a body. The header begins with a keyword and ends with a colon (

:). The body contains a series of other Python statements, all indented the same amount.Note

We will use the Python standard of 4 spaces for each level of indentation.

- condition¶

The boolean expression in a conditional statement that determines which branch is executed.

- conditional statement¶

A statement that controls the flow of execution depending on some condition. In Python the keywords

if,elif, andelseare used for conditional statements.- counter¶

A variable used to count something, usually initialized to zero and incremented in the body of a loop.

- cursor¶

An invisible marker that keeps track of where the next character will be printed.

- decrement¶

Decrease by 1.

- definite iteration¶

A loop where we have an upper bound on the number of times the body will be executed. Definite iteration is usually best coded as a

forloop.- delimiter¶

A sequence of one or more characters used to specify the boundary between separate parts of text.

- increment¶

Both as a noun and as a verb, increment means to increase by 1.

- infinite loop¶

A loop in which the terminating condition is never satisfied.

- indefinite iteration¶

A loop where we just need to keep going until some condition is met. A

whilestatement is used for this case.- initialization (of a variable)¶

To initialize a variable is to give it an initial value. Since in Python variables don’t exist until they are assigned values, they are initialized when they are created. In other programming languages this is not the case, and variables can be created without being initialized, in which case they have either default or garbage values.

- iteration¶

Repeated execution of a set of programming statements.

- loop¶

A statement or group of statements that execute repeatedly until a terminating condition is satisfied.

- loop variable¶

A variable used as part of the terminating condition of a loop.

- nested loop¶

A loop inside the body of another loop.

- nesting¶

One program structure within another, such as a conditional statement inside a branch of another conditional statement.

- newline¶

A special character that causes the cursor to move to the beginning of the next line.

- prompt¶

A visual cue that tells the user to input data.

- reassignment¶

Making more than one assignment to the same variable during the execution of a program.

- tab¶

A special character that causes the cursor to move to the next tab stop on the current line.

- trichotomy¶

Given any real numbers a and b, exactly one of the following relations holds: a < b, a > b, or a == b. Thus when you can establish that two of the relations are false, you can assume the remaining one is true.

- trace¶

To follow the flow of execution of a program by hand, recording the change of state of the variables and any output produced.