4. Conditionals and recursion¶

4.1. Modulus operator¶

The modulus operator works on integers (and integer expressions) and yields

the remainder when the first operand is divided by the second. In C++, the

modulus operator is a percent sign, %. The syntax is exactly the same as

for other operators:

int quotient = 7 / 3;

int remainder = 7 % 3;

The first operator, integer division, yields 2. The second operator yields 1, since 7 divided by 3 is 2 with 1 left over.

The modulus operater turns out to be surprisingly useful. For example, you can

check whether one number is divisible by another: if x % y is zero, then

x is divisible by y.

Also, you can use the modulus operator to extract the rightmost digit or

digits from a number. For example, x % 10 yields the rightmost digit of

x (in base 10). Similarly x % 100 yields the last two digits.

4.2. Logical operators¶

There are three logical operators in C++: AND, OR, and NOT, which are

denoted by the symbols &&, ||, and ! respectively. The semantics

(meaning) of these operators is similar to their meaning in English. For

example, x > 0 && x < 10 is true only if x greater than zero AND less

than 10.

4.3. The bitwise operators¶

C++ has a set of bitwise operators that operate on integer types, treating the operands as a sequence of bits.

The bitwise not operator flips the bits, replacing 0 bits with 1

and 1 bits with 0.

The bitwise and, or and exclusive or take two operands and return

a bitwise result as described in the following table:

Name |

Symbol |

Description |

|---|---|---|

AND |

|

1 if both operand bits are 1, otherwise 0 |

OR |

|

1 if at least one operand bit is 1, 0 if both operand bits are 0 |

XOR |

|

1 if at exactly one operand bit is 1, otherwise 0 |

NOT |

|

1 if operand bit is 0, 0 if operand bit is 1 |

Two other bitwise operators, left shift and right shift, each take two arguments. The first (left) argument is shifted left or right by the number of bits given in second (right) argument.

Name |

Symbol |

Description |

|---|---|---|

Left Shift |

|

|

Right Shift |

|

|

We will explore these operators further in the exercises.

4.4. Conditional execution¶

In order to write useful programs, we almost always need the ability to check

certain conditions and change the behavior of the program accordingly.

Conditional statements give us this ability. The simplest form is the

if statement:

if (x > 0) {

cout << "x is positive" << endl;

}

The expression in parentheses is called the condition. If it is true, then the statements in brackets get executed. If the condition is not true, nothing happens.

The condition can contain any of the comparison operators:

x == y // x equals y

x != y // x is not equal to y

x > y // x is greater than y

x < y // x is less than y

x >= y // x is greater than or equal to y

x <= y // x is less than or equal to y

Although these operations are probably familiar to you, the syntax C++ uses is a little different from mathematical symbols like =, ≠ and ≤. A common error is to use a single = instead of a double ==. Remember that = is the assignment operator. Also, there is no such thing as =< or =>.

The two sides of a comparision operator have to be the same type. You can only

compare ints to ints, and doubles to doubles. Comparing

strings is more complicated, so we will put that off until we get to the

Strings chapter.

4.5. Boolean values¶

The types we have seen so far are pretty big. There are a lot of integers and

floating-point numbers. By comparision, the set of characters is pretty small.

Well there is another type in C++ that is even smaller. The boolean data

type has only two values, true and false.

Without thinking about it, we have been using boolean values for the last

few chapters. The condition inside an if statement or a while

statement is a boolean expression. Also, the result of a comparision

operator is a boolean value. For example:

if (x == 5) {

// do something

}

The operator == compares two integers and produces a boolean value.

The values true and false are keywords in C++, and can be used

anywhere a boolean expression is called for. For example,

while (true) {

// loop forever

}

is a standard idiom for a loop that should run forever (or until it reaches

a return or break statement).

4.6. Boolean variables¶

As usual, for every type of value, there is a corresponding type of variable. In C++ the boolean type is called bool. Boolean variables work just like the other types:

bool george;

george = true;

bool test_result = false;

The first line is a simple variable declaration; the second line is an assignment, and the third line is a combination of a declaration and an assignment, called an initialization.

As we mentioned, the result of a comparision operator is a boolean, so you can

store it in a bool variable

bool even_flag = (n%2 == 0); // true if n is even

bool positive_flag = (n > 0); // true if n is positive

and then use it as part of a conditional statement later

if (even_flag) {

cout << "n was even when I checked it" << endl;

}

A variable used in this way is called a flag, since it flags the presence or absence of some condition.

even_flag || n%3 == 0 is true if either of the conditions is true, that

is, if even_flag is true OR the number is divisible by 3.

Finally, the NOT operator has the effect of negating or inverting a boolean

expression, so !even_flag is true if even_flag is false, that is, if

the number is odd.

Logical operators often provide a way to simplify nested conditional statements. For example, the following nested if statements could be written as a single conditional:

if (age > 16) {

if (age < 65) {

cout << "age is within the normal working age." << endl;

}

}

It will be left as an exercise for you to do this.

4.7. Numbers as boolean values¶

In C++ numeric values can be used as boolean expressions. When used in this way, zero values are false, and any nonzero value is true.

if (4)

cout << "Nonzero values are true." << endl;

if (0.0)

cout << "I'm true." << endl;

else

cout << "I'm false." << endl;

This code segment will print “Nonzero values are true.” and “I’m false.”

4.8. Alternative execution¶

A second form of conditional execution is alternative execution, in which there are two possibilities, and the condition determines which one gets executed. The syntax looks like:

if (x % 2 == 0) {

cout << "x is even" << endl;

} else {

cout << "x is odd" << endl;

}

If the remainder when x is divided by 2 is zero, then we know that x is even, and the is code displays a message to that effect. If the condition is false, the second set of statements is executed. Since the condition must be true or false, exactly one of the alternatives will be executed.

Alternative execution is so common that C++ has a built-in operator for it. Using the conditional operator the previous four lines can be written in one.

cout << (x % 2 == 0 ? "x is even" : "x is odd") << endl;

The first operand in this so called ternary operator is a condition

followed by a question mark and then two values separated by a colon. If the

condition is true, the operand immediately after the ? is returned,

otherwise the one after the : is returned.

This example provides us with another opportunity to talk about the usefulness of functions. If you think you might want to check the parity (eveness or oddness) of numbers often, you could “wrap” this code in a function, like this:

void print_parity(int x) {

cout << (x % 2 == 0 ? "x is even" : "x is odd") << endl;

}

Now we have a function named print_parity that will display an appropriate

message for any integer we care to provide. In our main function we would

call this function like this:

print_parity(17);

4.9. Chained conditionals¶

Sometimes you want to check for a number of related conditions and choose one

of several actions. One way of doing this is by chaining a series of

ifs and elses:

if (x > 0) {

cout << "x is positive" << endl;

} else if (x < 0) {

cout << "x is negative" << endl;

} else {

cout << "x is zero" << endl;

}

In this example, the

law of trichotomy

guarantees that if x is neither greater than nor less than zero, we know

that it is zero, so in the third branch of our conditional we only need

an else.

These chains can be as long as you want, although they can be difficult to read if they get out of hand. One way to make them easier to read is to use standard indentation, as we have demonstrated. If you keep all the statements and curly-braces lined up, you are less likely to make syntax errors and you can find them more quickly if you do.

4.10. The switch statement¶

The switch statement is used when you want different actions to occur based on specific values of an evaluated expression.

char choice = 'C';

switch (choice) {

case 'A':

cout << "You chose A" << endl;

break;

case 'B':

cout << "You chose B" << endl;

break;

case 'C':

cout << "You chose C" << endl;

break;

case 'D':

cout << "You chose D" << endl;

break;

default:

cout << "You didn't make a valid choice" << endl;

break;

}

Running this code segment will cause “You chose C” to be printed. The break statements cause the switch statement to end and are required. Without them the output would be:

You chose C

You chose D

You didn't make a valid choice

Try running this code after removing all the break statements to confirm

that this is true.

4.11. Nested conditionals¶

In addition to chaining, you can also nest one conditional within another. We could have written the previous example as:

if (x == 0) {

cout << "x is zero" << endl;

} else {

if (x > 0) {

cout << "x is positive" << endl;

} else {

cout << "x is negative" << endl;

}

}

There is now an outer conditional that contains two branches. The first branch

contains a simple output statement, but the second branch contains another

if statement, which has two branches of its own. Fortunately, those two

branches are both output statements, although they could have been conditional

statemtents as well.

Notice again that indentation helps make the structure apparent, but nevertheless, nested conditionals get difficult to read very quickly. In general, it is a good idea to avoid them when you can.

On the other hand, this kind of nested structure is common, and we will see it again often.

4.12. Truth and numbers¶

As the following program shows, numbers in C++, both integers and floating point numbers, can be used as boolean values and are false when they are equal to zero and true otherwise.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void print_true_or_false(int n) {

if (n)

cout << "The variable with value " << n << " is true." << endl;

else

cout << "The variable with value " << n << " is false." << endl;

}

void print_true_or_false(double n) {

if (n)

cout << "The variable with value " << n << " is true." << endl;

else

cout << "The variable with value " << n << " is false." << endl;

}

int main()

{

int i = 4;

double d = -2.0;

print_true_or_false(i);

print_true_or_false(d);

i = 0;

d = 0;

print_true_or_false(i);

print_true_or_false(d);

return 0;

}

Run this program and observe the output.

4.13. The return statement¶

The return statement allows you to terminate the execution of a function

before you reach its end. One reason to use it is if you detect an error

condition:

#include <cmath>

void print_logarithm(double x) {

if (x <= 0.0) {

cout << "Positive numbers only, please." << endl;

return;

}

double result = log(x);

cout << "The log of x is " << result << endl;

}

This defines a function named print_logarithm that has a double named x

as a parameter. The first thing it does is check whether x is less than or

equal to zero, in which case it displays an error message and then uses

return to exit the function. The flow of execution immediately returns to

the caller and the remaining lines of the function are not executed.

We used a floating-point value on the right side of the condition because there is a floating-point variable on the left.

Remember that any time you want to use a function from the math library, you have to include the header file

cmath, which we have included here as a reminder.

4.14. Recursion¶

We mentioned in the last chapter that it is legal for one function to call another, and we have seen several examples of that. We neglected to mention that it is also legal for a function to call itself. It may not be obvious why that is a good thing, but it turns out to be one of the most magical and interesting things a program can do.

For example, look at the following function:

void countdown(int n) {

if (n == 0) {

cout << "Blastoff!" << endl;

} else {

cout << n << endl;

countdown(n-1);

}

}

The name of the function is countdown and it has a single integer

parameter. If the parameter is zero, it outputs the word “Blastoff!”.

Otherwise, it outputs the parameter and then calls a function named

countdown - itself - passing n-1 as an argument.

What happens if we call this function like this:

int main()

{

countdown(3);

return 0;

}

The execution of countdown begins with n=3, and since n is not zero,

it outputs the value 3, then calls itself…

The execution of

countdownbegins with n=2, and since n is not zero, it outputs the value 2, then calls itself…The execution of

countdownbegins with n=1, and since n is not zero, it outputs the value 1, then calls itself…The execution of

countdownbegins with n=0, and since n is zero, it outputs the word “Blastoff!” and then returns.The

countdownthat got n=1 returns.The

countdownthat got n=2 returns.

The countdown that got n=3 returns.

And then we’re back in main (what a trip!), so the total output looks

like:

3

2

1

Blastoff!

As a second example, let’s look again at the functions new_line and

three_lines.

void new_line() {

cout << end;

}

void three_lines() {

new_line(); new_line(); new_line();

}

Although these work, they would not be much help if we wanted to output 2 newlines, or 42. A better alternative would be:

void n_lines(int n) {

if (n > 0) {

cout << endl;

n_lines(n-1);

}

}

This function is similar to countdown; as long as n is greater than zero,

it outputs one newline, and then calls itself to output n-1 additional

newlines. Thus the total number of newlines is 1 + (n - 1), which comes out to

n, just like we wanted.

The process of a function calling itself is called recursion, and such functions are said to be recursive.

4.15. Infinite recursion¶

In the examples in the previous section, notice that each time the functions get called recursively, the argument gets smaller by one, so eventually it gets to zero. When the argument is zero, the function returns immediately, without making any recursive calls. This case - when the function completes with making a recursive call - called the base case.

If a recursion never reaches a base case, it will go on making recursive calls forever and the program will never terminate. This is known as infinite recursion, and is generally not considered a good idea.

In most programming environments, a program with infinite recursion will not really run forever. Eventually, something will break and the program will report an error. You will explore this first example we have seen of a run-time error in the exercises.

4.16. Stack diagrams for recursive functions¶

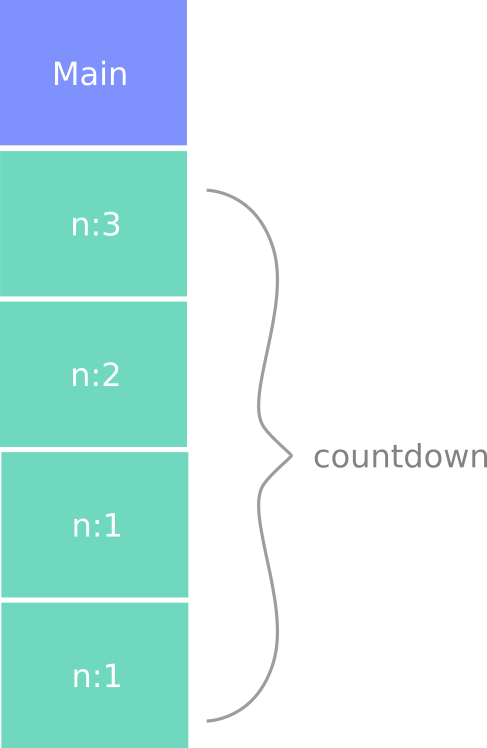

In the previous chapter we used a stack diagram to represent the state of a program during a function call. The same kind of diagram can make it easier to interpret a recursive function.

Remember that every time a function gets called it creates a new instance that contains the function’s local variables and parameters.

This figure shows a stack diagram for countdown, called with n = 3:

There is one instance of main and four instances of countdown, each

with a different value for the parameter n. The bottom of the stack,

countdown with n = 0, is the base case. It does not make a recursive

call, so there are no more instances of countdown.

The instance of main is empty because main does not have parameters or

local variables.

4.17. Glossary¶

- chaining¶

A way of joining several conditional statements in sequence.

- conditional¶

A block of statements that may or may not be executed depending on some condition.

- infinite recursion¶

A function that calls itself recursively without ever reaching the base case. Eventually an infinite recursion will cause a run-time error.

- modulus operator¶

An operator that works on integers and yields the remainder when one number is divided by another. In C++ it is denoted with a percent sign (

%).- nesting¶

Putting a conditional statement inside one or both branches of another conditional statement.

- recursion¶

The process of calling the same function you are currently executing.